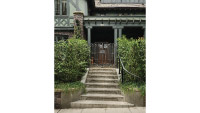

Bloch Residence

The Bloch residence is a stunningly well-preserved Tudor-revival home that fronts onto Volunteer Park in Capitol Hill. Built in 1908, it was the first collaboration by the architectural partnership of Clayton D. Wilson and Arthur Loveless. Our design work focused primarily on revitalizing the site. The east yard was envisioned as a condensed English garden on an urban site. A new retaining wall and fence were built just inside the historic perimeter wall, to enlarge the private outdoor space. The original east porch was enclosed with glazed steel panels. A new tiled fountain wall incorporating a Swiss stone basin was constructed on-axis with the public rooms of the house. Geometric on-edge slate paving emphasized this axiality.

Indoors, modern kitchen cabinets were replaced with custom wood cabinets that incorporated historic detailing. Original tile was replicated to fill in a missing portion of the historic kitchen wainscot. All five fireplaces were refurbished to ensure their safe operation, which included reconstructing the Rathskeller fireplace closely following the original. Building systems and aged plumbing fixtures were also refurbished or replaced.

In December 2023, the Bloch residence was designated a City of Seattle Landmark on three criteria. The exterior, the site, and several interior spaces are now protected. On behalf of the current owners, we prepared the nomination and helped them to realize special tax valuation benefits for their renovation.

To learn more, please refer to the Report on the Landmark Designation.

Germania Hall at Second Avenue and Seneca Street, c. 1903 (Image source: MOHAI, Seattle Businesses and Buildings Photograph Album, 1972.5346.7)

Wilhelm [William] Karl Bloch and his wife Minna Mishke were both German immigrants who met in Seattle and wed in 1891. In January 1898, Bloch became the proprietor of the new Germania Café situated in the ground floor of Germania Hall at the southeast corner of Second Avenue and Seneca Street. Built by the Seattle Brewing and Malting Company, Germania Hall consolidated Seattle’s German social communities within one establishment. Bloch held the lease to the entire building.

Billy Bloch was an astute businessman with a carefully crafted public persona as the quintessential German. His endearing qualities – “his foresight, his genial good humor and his rugged honesty” – allowed Bloch “to build up a large clientage of friends.” After the German organizations outgrew Germania Hall, Bloch teamed up with Alexander Pantages, the emerging vaudeville magnate, and his architect Clayton Wilson to convert the vacant upper floors into the Lois Theater which opened in October 1906.

That same month, Minna purchased the parcel at the corner of Fifteenth Avenue and Prospect Street for $5,000. A foundation permit for their home was taken out in January 1908 followed by a building permit for a $10,000 two-story frame dwelling the next month. Wilson was again given the commission, which aligned fortuitously with Wilson’s partnership with Arthur Loveless. The Bloch residence was celebrated for its “splendid” magnificence as soon as it was completed. The Blochs were living the high life at the outset of the teens, but their fate would soon change.

The first blow came on December 19, 1911 when a fire started in the kitchen of the Germania Café. The café reopened just two days later, but the Lois was a total loss that Pantages would not rebuild. Then statewide prohibition was enacted in January 1916, and the Germania Café faced a dry squad raid. The biggest impact, though, came from the virulent anti-German sentiment that swept the country as World War I drew near.

Billy Bloch’s cultivated prototypical-German image that had once driven his success was now contributing to his downfall. Bloch was even referred to the Department of Justice in January 1918 for “again voicing sentiments inimical to this country.” The complaint was ultimately dismissed but the report on the matter evidences how drastically sentiments had shifted.

It was in this combined storm of prohibition and anti-Germanism that “Billy Bloch’s eatery [closed] its hospitable efforts forever” in May 1917. Bloch tried to recapture success in the Orpheum soda shop where he faced dry squad raids of both his home and business. In the final raid of the Orpheum in February 1918, a small quantity of whiskey and “two sections of a German flag” were found behind the bar. “Kultur in its most exalted form was practiced” that afternoon, when “a corps of officers […] took out everything [from the café] that was not nailed down, and those things that were, they smashed with axes.” Bloch was convicted on a bootlegging charge for that raid in March 1918.

Two weeks after Bloch was convicted, their “palatial Capitol Hill residence” was sold in “what [was] regarded by realty men as the most important private-home sale of the entire year.” It was a rapid and unceremonious end to Bloch’s era of prosperity. After a brief stint in Chicago, the Blochs purchased a modest home facing onto Greenlake where they lived until their deaths. Billy Bloch, “one of the most picturesque and beloved figures of early [Seattle],” died on October 30, 1931 and Minna followed twelve years later.

Wilson and Loveless, Architects

When the Bloch Residence appeared in the Washington AIA’s architectural exhibition in May 1908, it was the first known introduction of the new partnership of Clayton D. Wilson and Arthur Loveless. While Wilson’s work was well known to Seattleites, Loveless had just arrived in Seattle the previous autumn. The Bloch Residence was not only an auspicious first project for the partnership, it was a remarkable introduction to Seattle of Arthur Loveless, who would become one of the city’s preeminent architects.

Clayton Danforth Wilson began working as an architect when he moved to Los Angeles in 1892, and partnered with Louis L. Mendel during this period. Around the turn of the century, Wilson moved to Seattle and by 1901 was a draftsman in the firm of Charles Bebb and Louis Mendel. In 1902, Wilson formed his own firm that would design several notable buildings, including the Seattle Municipal Building (now the Public Safety Building), which he won in competition against eight other architects. He also completed several early projects for both William Bloch and Alexander Pantages. Wilson’s single-family residences during this time were well-proportioned and well-detailed, revealing the hand of an experienced architect.

Arthur Lamont Loveless entered the school of architecture at Columbia University in the fall of 1902 at a time when changes influenced by the École des Beaux-Arts were sweeping through architectural education. Loveless later joined the advanced design atelier of William Adams Delano who ran a distinguished practice of Delano & Aldrich. Loveless left Columbia before receiving a diploma in the spring of 1906 and spent about a year working for that firm. In January 1907, an entry submitted by Loveless under the name “Delano, Aldrich, & Lovelace” was favored in the design competition for a new City Hall at Montpelier, Vermont. Whether “Delano, Aldrich & Lovelace” was merely a tactic to impress the committee or truly represented Loveless’s standing with the partners is unknown but it speaks to his tremendous talent. They were ultimately not awarded the City Hall commission and Loveless left New York for Europe in May 1907.

Wilson & Loveless Architects, Partnership 1907-1911

Clayton Wilson and Arthur Loveless probably began collaborating on the Bloch residence shortly after Loveless arrived in Seattle in late 1907. Although it is impossible to know the exact roles Wilson and Loveless each played in its design, that Loveless was more than a draftsman for Wilson is evident: the floor plan is ordered, spatially coherent, and nearly symmetrical with well-proportioned rooms that connect more gracefully than those in Wilson’s own residential designs. Wilson crediting Loveless in the Washington AIA Exhibition catalog also speaks to their roles as equals in the design of the house.

By the summer of 1908, projects attributed to “Wilson & Loveless, Architects” began appearing in Seattle periodicals and over the next four years the partners completed more than 40 buildings together. More than half of the projects produced under the name Wilson & Loveless were single family residences. Perhaps their best known of these was the lavish residence built in Madison Park for Pantages.

Similarity in plan arrangement, clarity in the organization of rooms made legible on the building exterior, and richness in detail amidst diversity in style all suggest that academically-trained Arthur Loveless may have taken the lead in design of these large custo homes. Wilson & Loveless’s residential work was quickly recognized and published, most notably in a series of House Beautiful articles during 1911 and 1912 that promoted several of their homes – including Bloch and Pantages – as good examples to be studied and emulated.

At the end of 1911, Loveless left Seattle for “an extended trip through the East,” returning in March 1912. Instead of rejoining Wilson in the Arcade Annex, though, Loveless elected to establish an office in the Henry Building and the partnership of Wilson & Loveless Architects was dissolved. No reason for the dissolution has been located.

After Loveless left the partnership, Wilson returned to working as a solo practitioner. Wilson’s architectural practice was never again as busy as it was while in partnership with Loveless though. In 1916 he unsuccessfully applied for the position of City Architect, and through the 1920s and 1930s he worked in various positions for the City of Seattle. In the late 1930s, Wilson moved with his second wife to Port Gamble. Following her death in 1944, Clayton Wilson moved to the Masonic Home in Zenith where he passed away at age 81 on April 9, 1947.

The later architectural career of Arthur Loveless is well known, and by the 1920s he appeared regularly in the Seattle press as one of the city’s leading architects. On his return to Seattle in 1912, Loveless briefly shared an office with Andrew Willatzen before partnering with Daniel R. Huntington, the recently-appointed City Architect. From 1915, when he began independent practice, until retirement in the late 1930s, Loveless designed over 70 single-family residences amongst several other notable projects. Perhaps his best-known building is the eponymous 1930 Loveless Studio Building at the north end of Capitol Hill’s Broadway District where Loveless’s own office was to be found. In 1936, he partnered with his protégé Lester P. Fey to become Loveless & Fey. When Daniel Lamont joined the firm in 1940, the name changed again to Loveless, Fey & Lamont. Arthur Loveless appears to have withdrawn from active involvement in the firm around 1937 and he passed away in January 1971 at age 97.